From: ontolog-forum-bounces@xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx [mailto:ontolog-forum-bounces@xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx]

On Behalf Of Bruce Schuman

Sent: Wednesday, April 02, 2014 4:39 PM

To: '[ontolog-forum] '

Subject: Re: [ontolog-forum] Hermeneutics and semiotics (was FWD: mKR2IKL)

Ah so J

Yes, my careless understatement has triggered some interesting thoughts. I was vaguely aware when I wrote that sentence that my comment was a gross oversimplification, but the point seemed minor compared to the issue I wanted to explore.

But so be it. Edward is absolutely right, and I wrote him a brief private note saying that much, and thanking him – but since the theme has some momentum, I’ll add a response.

Edward’s summary of factors contributing to the renaissance is illuminating and succinct. It would be interesting to go through every one of the factors he cites and consider what implications there might be for “semantic ontology”. How

did these people in those days understand the meaning of abstraction? How did their emerging model of “the science / religion dialogue” position these subject areas, and how did they relate to one another? Were they purely and bitterly antithetical and combative,

as some still see them today – or simply in entirely separate non-relating categories (“silos”) -- or were they, as some modern theologians would suggest – complementary facets of a single cosmology or world-view? If they saw them as complementary – what

kind of models did they develop to explain this emerging relationship? Did they see them – as I might – as occupying “different levels of abstraction?” Those questions are still very much on the table today….

> So far so good. The process is partly sequential in time; I think it tends to be more of a helical spiral in content, but I am not a philosopher.

It would be interesting to see some sketch of this helical spiral – with some labels. What is varying – what are the dimensions of the spiral? If one of the dimensions is time – what is it that is spiraling?

> Putting it very simply, science emerged in the renaissance in response to ideological religious claims ("the sun revolves around the earth").

(that probably should have read “putting it much too simply – and leaving out many other factors”)

This is definitely a sidebar, and I would argue that it is vastly oversimplified. Science emerged in Renaissance Europe out of human curiosity about the nature of things. The emergence is a consequence of many

factors:

- the rise of a middle class, or at least an economy that was not primarily about subsistence, which created the opportunity for cultural growth;

- the growth of universities, which, in spite of their often ecclesiastical foundations, taught students to think and made them familiar with much of the classical literature;

- the spread of scientific and mathematical knowledge into Europe from China, India and the Islamic intellectual centers;

- Gutenberg’s movable type, which made possible the broad dissemination of new ideas faster than the Church and State powers could rein them in;

- the development of European postal services, which enabled communication among far-flung intellectual communities;

- the development of materials knowledge (an outgrowth of alchemy) and engineering technologies, which made many scientific observations possible.

Interesting that two of these factors involve “internet-like” aspects – of information-dissemination: moveable type / printing – and postal services

(ok, comparing this to the internet is another somewhat careless analogy – but there is at least one major dimension in common – the significant empowerment of new forms of information transmission)

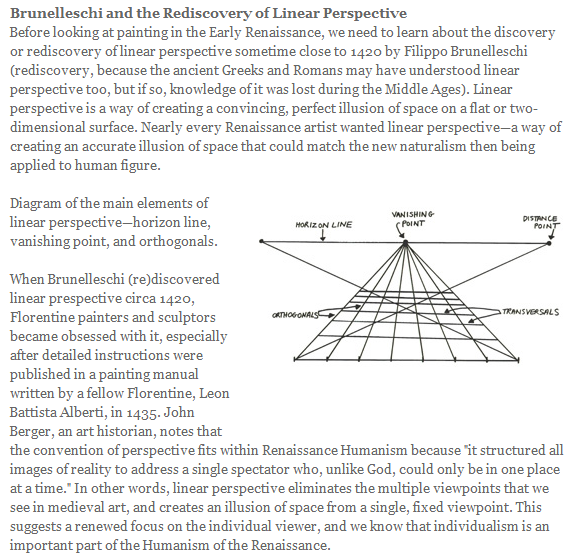

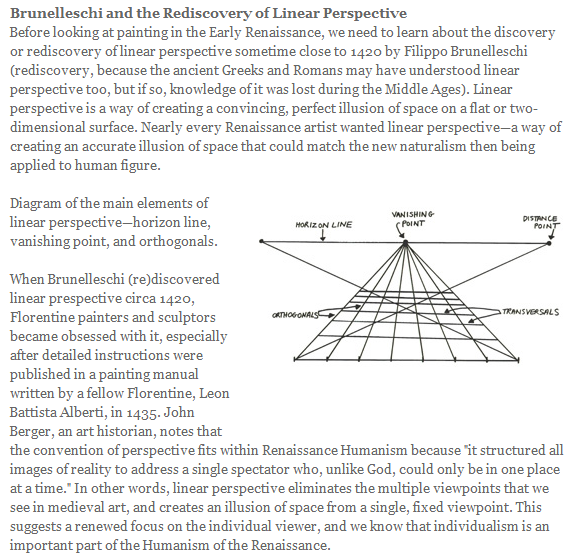

When I took a course in art history many years ago, a major issue was “the discovery of perspective”. Google that phrase and there’s a lot to be found .

My understanding is – when perspective was conceptualized – it literally changed cognition and perception as well.

This below comment suggests that “the convention of perspective fits within Renaissance Humanism because ‘it structured all images of reality to address a single spectator who, unlike God, could only be in one

place at a time.’ In other words, linear perspective eliminates the multiple viewpoints that we see in medieval art, and creates an illusion of space from a single, fixed viewpoint. This suggests a renewed focus on the individual viewer, and we know that individualism

is an important part of the Humanism of the Renaissance.”

http://smarthistory.khanacademy.org/Brunelleschi.html

Bruce,

While you are keeping the discussion coherent, I think you wandered a bit off-track here:

> I tend to see the growth of philosophy as an evolutionary process that takes place in sequential stages. In a specific historical context and body of philosophical/cultural assumptions -- some new perspective emerges, partly informed

by the context, partly in reaction to some perceived weakness in it.

So far so good. The process is partly sequential in time; I think it tends to be more of a helical spiral in content, but I am not a philosopher.

> Putting it very simply, science emerged in the renaissance in response to ideological religious claims ("the sun revolves around the earth").

This is definitely a sidebar, and I would argue that it is vastly oversimplified. Science emerged in Renaissance Europe out of human curiosity about the nature of things. The emergence is a consequence of many

factors:

- the rise of a middle class, or at least an economy that was not primarily about subsistence, which created the opportunity for cultural growth;

- the growth of universities, which, in spite of their often ecclesiastical foundations, taught students to think and made them familiar with much of the classical literature;

- the spread of scientific and mathematical knowledge into Europe from China, India and the Islamic intellectual centers;

- Gutenberg’s movable type, which made possible the broad dissemination of new ideas faster than the Church and State powers could rein them in;

- the development of European postal services, which enabled communication among far-flung intellectual communities;

- the development of materials knowledge (an outgrowth of alchemy) and engineering technologies, which made many scientific observations possible.

The collision with unfounded doctrine about the natural world was inevitable, but that doctrine, and the power of its adherents, was only the cause of the resulting fireworks, not the cause of the intellectual

movement. Even when you look at the work of Luther and Calvin and (earlier) Savonarola, their complaint was about the abuses of power and doctrine, both theological and non-theological, and the suppression of intellectual thought in general, not about its

relationship to the natural world. Scientists like Galileo and Brahe reported the results of experiments. They were aware that they contradicted the teachings of the Church, but they didn’t undertake the experiments in order to disprove the teachings; they

undertook the experiments in order to know the workings of the natural world.

-Ed

--

Edward J. Barkmeyer Email:

edbark@xxxxxxxx

National Institute of Standards & Technology

Systems Integration Division

100 Bureau Drive, Stop 8263 Work: +1 301-975-3528

Gaithersburg, MD 20899-8263 Mobile: +1 240-672-5800

"The opinions expressed above do not reflect consensus of NIST,

and have not been reviewed by any Government authority."

Just to keep this coherent -- let me focus on one single issue/question.

You say that a vague or fuzzy idea is/might be *better* than a precise one.

I have to speculate to guess what you mean by that.

Can you give an example?

***

I tend to see the growth of philosophy as an evolutionary process that takes place in sequential stages. In a specific historical context and body of philosophical/cultural assumptions -- some new perspective emerges, partly informed

by the context, partly in reaction to some perceived weakness in it. Putting it very simply, science emerged in the renaissance in response to ideological religious claims ("the sun revolves around the earth"). If I got this right, the Vienna Circle -- Carnap

et al -- more less asserted that any statement that does not have an unambiguous empirical interpretation is "meaningless" -- probably asserting this in reaction to perceived cultural/philosophic weaknesses that they may have seen as dangerous and misleading.

Logical analysis shows that there are two different kinds of statements; one kind includes statements reducible to simpler statements about the empirically given; the other kind includes statements which cannot

be reduced to statements about experience and thus they are devoid of meaning. Metaphysical statements belong to this second kind and therefore they are meaningless. Hence many philosophical problems are rejected as pseudo-problems which arise from logical

mistakes, while others are re-interpreted as empirical statements and thus become the subject of scientific inquiries.

One source of the logical mistakes that are at the origins of metaphysics is the ambiguity of natural language. "Ordinary language for instance uses the same part of speech, the substantive, for things ('apple')

as well as for qualities ('hardness'), relations ('friendship'), and processes ('sleep'); therefore it misleads one into a thing-like conception of functional concepts".[6] Another source of mistakes is "the notion that thinking can either lead to knowledge

out of its own resources without using any empirical material, or at least arrive at new contents by an inference from given states of affair".[7] Synthetic knowledge a priori is rejected by the Vienna Circle. Mathematics, which at a first sight seems an example

of necessarily valid synthetic knowledge derived from pure reason alone, has instead a tautological character, that is its statements are analytical statements, thus very different from Kantian synthetic statements. The only two kinds of statements accepted

by the Vienna Circle are synthetic statements a posteriori (i.e., scientific statements) and analytic statements a priori (i.e., logical and mathematical statements).

However, the persistence of metaphysics is connected not only with logical mistakes but also with "social and economical struggles".[8] Metaphysics and theology are allied to traditional social forms, while

the group of people who "faces modern times, rejects these views and takes its stand on the ground of empirical sciences".[8] Thus the struggle between metaphysics and scientific world-conception is not only a struggle between different kinds of philosophies,

but it is also—and perhaps primarily—a struggle between different political, social, and economical attitudes.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Vienna_Circle#Manifesto

That metaphysics is meaningless was a pretty strong claim -- and maybe contributed a lot to the discrediting of intuition and the vague metaphysics that goes with it.

But the evolutionary force of philosophical growth and deep human instinct keeps the themes alive -- and philosophers come along who assert that there IS real content in deep intuition -- and we're going to invent an explanation and

try to prove it to you.

So -- a new school of less exact thinkers who tend to trust intuition create things like "hermeneutics" and "semiotics" -- which look to me like intuitive stabs at something like cognitive science -- developed by guys with good brains

but no real scientific precision (maybe because no scientific precision was yet available to them, at least in terms they could understand or really use). So they build this stuff and get students and followers and universities to honor it, create courses

on it, publish books, etc., and it gets taken seriously in philosophy departments. They build entire systems of interlocking definitions – all written in “floating variables”, none of which have clear-cut empirical grounding.

My instinct is -- give these guys a break. They are pioneers. They are pushing for clarity in areas we don't understand very well -- so their stuff is like an initial exploratory hypothesis. Let's look at their content, and see if

we can explain it better -- the way the heliocentric theory of the solar system replaced the earth-centric model. Their theories are “interim stages” along the way…

***

So, my question would be -- why/how is a fuzzy or ambiguous statement in natural language somehow better than a formal/strict statement -- (if the formal statement does not actually "lose information", but actually contains and represents

the entire content of the fuzzy statement)? Maybe you are saying that the formal/strict method *cannot* represent the intuitive idea without loss of information or content.

Please give an example -- because I don't really understand this. Maybe the multiple-branching interpretations of the fuzzy statement are considered "good"? To me, this is kind of like the argument that there is no official interpretation

of a work of art -- people get to see it any way they like, and endlessly discuss alternative meanings.

(yes, this is a complicated subject -- thanks for looking at this)

> The Wikipedia comments on Schleiermacher illustrate this issue.

> “Hermeneutics is the art of avoiding misunderstanding”. An art, not a

> science. So – at some point, I would say, this task of “translating”

> the broadly intuitive (and perhaps fuzzy) ideas of the liberal arts

> into precisely unambiguous scientific definitions has still not been

> accomplished.

John:

You can't translate a vague or fuzzy idea into a precise one without changing it. Sometimes the vague idea is *better* or more appropriate than any attempted translation. That's the major strength of natural languages -- you can continue

to use the same words for the full continuum from vague to precise.

Bruce Schuman

NETWORK NATION: http://networknation.net

SHARED PURPOSE: http://sharedpurpose.net

INTERSPIRIT: http://interspirit.net

(805) 966-9515, PO Box 23346, Santa Barbara CA 93101

-----Original Message-----

From: ontolog-forum-bounces@xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx [mailto:ontolog-forum-bounces@xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx] On Behalf Of John F Sowa

Sent: Tuesday, April 01, 2014 7:41 AM

To: ontolog-forum@xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx

Subject: [ontolog-forum] Hermeneutics and semiotics (was FWD: mKR2IKL)

Bruce,

You raised some important issues. They are fundamental to logic and ontology. I changed the subject line to indicate a change in topic.

> I see subject areas like "hermeneutics" or "semiotics" as examples --

> which look to me like attempts to create scientific or strict

> interpretations of abstractions, but without the benefit of a

> well-grounded precision -- the way a biologist might ground ideas in

> chemistry, which in turn might be grounded in physics.

That's why I cited Peirce. He founded the field of semiotics, and he stands head and shoulders above the rest -- primarily because he covered the whole field *in depth*.

He used precise logic and math in science. But he also worked as an associate editor for the _Century Dictionary_, for which he wrote, revised, or edited over 16,000 definitions. He understood both ends.

> I was interested in the interpretation of broad abstractions, like

> those considered in hermeneutics. But I took a critical and skeptical

> view of their methods, convinced that their approach would never lead

> to “reliable and trustworthy results” – so, without changing the

> subject matter (deep intuition and holistic

> thinking) my methods migrated to computer science.

That's important. There are three kinds of logicians -- and the same classification could be applied to any branch of science:

1. Those who make important contributions by solving hard problems

and narrow the field to problems they know how to solve.

2. Those who understand the full continuum. They have solved hard

problems, they know what it means to solve a problem, and they

do their best to extend the field.

3. Those who have solved some hard problems, but criticize those

who try to extend the boundaries beyond the safe and secure.

Among the pioneers, Frege, Russell, and Carnap are the first kind.

Peirce, Whitehead, and Wittgenstein belong to the second kind.

Quine is an example of the third. He criticized innovations even by his mentor and best buddy, Carnap. One of his former students, Hao Wang, called Quine's philosophy "logical negativism".

> The Wikipedia comments on Schleiermacher illustrate this issue.

> “Hermeneutics is the art of avoiding misunderstanding”. An art, not a

> science. So – at some point, I would say, this task of “translating”

> the broadly intuitive (and perhaps fuzzy) ideas of the liberal arts

> into precisely unambiguous scientific definitions has still not been

> accomplished.

You can't translate a vague or fuzzy idea into a precise one without changing it. Sometimes the vague idea is *better* or more appropriate then any attempted translation. That's the major strength of natural languages -- you can continue

to use the same words for the full continuum from vague to precise.

Peirce, (CP 4.237)

> It is easy to speak with precision upon a general theme. Only, one

> must commonly surrender all ambition to be certain. It is equally easy

> to be certain. One has only to be sufficiently vague.

> It is not so difficult to be pretty precise and fairly certain at once

> about a very narrow subject.

When you express your precise scientific ideas in NLs, you can use the same words for centuries with precise, but changing definitions.

Look at physics -- the hardest of the hard sciences. The fundamental words -- mass, energy, force, momentum, space, time -- have had many precise, but changing definitions over the past several centuries.

In science, it's not a good idea to change the words every time you change the definition. URIs are good for finding documents, but I have very serious doubts about the philosophy of replacing vague words with supposedly "precise" URIs.

If you change your words with every change of meaning, you don't improve communication -- you destroy it.

> my primary question is “How do we avoid misunderstanding – in ‘human

> to human’ communication?”

Good question. Short answer: never.

Longer answer: Ask questions. Continue the dialog. As Peirce said, the fundamental rule of reason is "Do not block the way of inquiry."

John

_________________________________________________________________

Message Archives:

http://ontolog.cim3.net/forum/ontolog-forum/

Config Subscr:

http://ontolog.cim3.net/mailman/listinfo/ontolog-forum/

Unsubscribe:

mailto:ontolog-forum-leave@xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx

Shared Files: http://ontolog.cim3.net/file/ Community Wiki:

http://ontolog.cim3.net/wiki/ To join:

http://ontolog.cim3.net/cgi-bin/wiki.pl?WikiHomePage#nid1J