JS

> My main disagreement is with the emphasis on "one". In my 1984 book,

> the final chapter was "The Limits of Conceptualization". In my KR book (2000),

> Chapter 6 was "Knowledge Soup". There is no such thing as "one" ideal logic,

> ontology, methodology, classification scheme, or set of principles or primitives

> for deriving them.

>

> I won't deny the possibility that some infinite being (call it whatever you like --

> God, Nature, Logos, Tao, etc.) might have such a scheme.

> But no scheme that is humanly knowable can ever be complete.

>

> Gary raises some issues that illustrate this principle.

NET VERSUS TREE

The answer to this question -- "can we build a general model of conceptual structure?" -- no doubt depends on exactly what we are talking about -- and in the context of this Ontolog discussion, we might be talking about different things. If we mean "one formula to interpret every possible form of human thought in every possible empirical detail in every possible specific context for every purpose" -- no doubt that is "not humanly knowable" -- at least not in the sense that "we can build a computer that can do this". But if we shift the emphasis from the many differences among various theories and methods to a systematic search for the similarities among them, we might find quite a few.

I came across a book chapter from "Maps of the Mind" by Charles Hampden-Turner (100,000 copies sold in the USA, comprehensive survey book with 50+ diagrammatic approaches to cognitive/psychological models) that gets into the inherent psychological tension -- supposedly in every human being -- between "the net" and "the tree". The chapter discusses the work of psychologist Francesco Varela, who worked more recently with cognitive psychologist Eleanor Rosch.

http://bridgeacrossconsciousness.net/mindmaps/Map55.pdf

This net/tree tension seems to be a primary issue in any fully-inclusive/holistic psychological model -- and I think we see it here in this discussion -- in conflicting instincts for addressing the very evident "diversity" of methods and systems (the "net" model), and a contrary integrating drive to identify similarities and group processes together in one framework (the "tree" model). From the point of view of this Hampden-Turner chapter, picking one side of this argument might be a bit unbalanced. He suggests that we should see both sides, and address the strengths and weaknesses of either approach.

"The network is unbalanced by the purposively striving tree, and the tree rebalanced by the constraints of the network. We urgently need such a paradigm shift if the predatory nature of human purposes is not to wreck our ecology."

Gary

> William Frank went on to note that:

>

> Combinations of classifiers that are part of orthogonal classification

> schemes need to be accommodated in a different manner (most

> effectively, in my experience, through composition, but most commonly

> through "multiple inheritance" (but me, I do not know what

> "inheritance" means, except in biology and in class-oriented

> programming languages -- ((though I used to know, before I thought about it much)).

JS

> In that point, William was discussing automated methods for classifying

> things described by some kinds of features, attributes, properties, facets,

> or monadic relations. Arbitrary conjunction of such features generate a

> partial ordering. If you fill in the gaps of the partial ordering, you get a lattice.

QUANTITATIVE / QUALITATIVE

These comments point to another basic tension in cognitive models: the tension between quantitative and qualitative levels of description. If we draw a hierarchy or tree (or taxonomic) model of general conceptual structure, we have something like "quantitative dimensionality" at the bottom level, where objects and events can be described in terms of precise dimensional measurements -- but then, at higher levels of abstraction and generality, we run into abstract objects we call "properties" or "features" (or "characteristics" or "qualities" or "attributes" or "facets"). The cognitive science that I know about tends to see this tension as a critical divide -- and describes alternative theoretical approaches as "dimensional", "featural" or "holistic", which might be seen as inherently incommensurate.

This OCR transcription includes the first three chapters of Smith and Medin's influential 1981 "Categories and Concepts", which review these three approaches:

http://bridgeacrossconsciousness.net/docs/SmithAndMedinCh1.2.3.docx

To accommodate this change of variable type, there are a few different strategies. One is to look at the "levels of measurement" theory of Stanley Smith Stevens

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Level_of_measurement, which introduces ways to see abstract concepts as dimensional variables. Though it can get complicated for any kind of working model, it is also possible to do a "dimensional decomposition" (or analysis) of any of these holistic abstractions.

FEATURES ARE HOLISTIC OBJECTS

JS

> But if you look at most of those classification schemes, the so-called features

> or attributes are often described by English phrases that have a complex

> internal structure. That indicates some *hidden structure* that is

> independent of and not represented by the classification.

Yes, very much so. These terms called "features" are complex holistic objects with complex implicit or hidden structure, and the feature-term is a *name* for that structure -- in the same way that we might say that *any* concept-word is a name for a complex internal structure -- a complex internal structure that appears tacit or implicit, but which must be precisely analyzed if its meaning is uncertain or in question (speaking of birds, what is or is not a "chicken"?" list precise defining criteria here....)

The empirical point of view encounters the "feature-term" -- and sees it as inherently holistic and non-dimensional, and sees a fundamental incommensurateness, and tends to see the process of classification as necessarily fractured by this incommensurateness (“dimensions and features are inherently different”). But if we slow down, and clearly note the details of the basic holistic structure of a feature -- we can then apply the same kind of dimensional analysis to this abstract/holistic object, possibly through stipulative or negotiated definition. This further analysis of an undefined holistic object must be carried through if the classification process is to be fully accurate and widely understood.

The common taxonomy of birds lists the defining features as follows:

“Birds (class Aves or clade Avialae) are feathered, winged, bipedal, endothermic (warm-blooded), egg-laying, vertebrate animals.”

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bird

These terms – “feathered, winged, bipedal, endothermic (warm-blooded), egg-laying, vertebrate” – are all very holistic and “multi-dimensional”. In a shared social/scientific context like biological taxonomy, these terms are defined through a process of mutual consensus and negotiation, where every facet of each of these terms is critically examined from multiple points of view, seeking an optimal compromise that insofar as possible is “best for everybody” and as unambiguous as possible.

“What is or is not ‘feathered’?”

“What is ‘bi-pedal’?”

“What is ‘winged’?”

THE EXACT ANALYSIS OF HOLISTIC STRUCTURE

These questions can be addressed by crisp dimensional processes. “This object IS a feather, and this object is NOT a feather.” “How many feathers does it take for an animal to be ‘feathered’? Is one enough?” A dimensional envelope can be defined, within which the object (feather) must exist or it is not a member of that class or in that category. The dimensionality of a feather might be fairly complex, and involve a fair amount of negotiation. But in the analysis of the holistic defining term “feathered” for the broad class “bird”, this precision is essential or the definition will be confused and uncertain.

Gary

> Hacking makes his most critical comments on what he describes as its

> mis-application of classification schemes from Biology to mental illness.

> He stated it this way (note - NOS, stands for Not Otherwise Specified)...

JS

> I agree that NOS is a warning sign. It's the tip of an iceberg that has

> a huge amount of hidden structure.

Yes. “A huge amount of hidden structure” – where “hidden” means implicit or inherent and perhaps referenced by a single name or word.

But the task of the analyst is to uncover and explicitly reveal that implicit “hidden” structure.

My small thought is – we should not be disagreeing over whether this holistic structure exists within traditional classification schemes (since it clearly does). We should be clarifying the best analytical approach for considering the issues that are raised by this facet of natural and inherent symbolic/conceptual representation.

CLARIFY THE FOUNDATIONS

JS

> I like the following point:

Ian Hacking -- http://www.lrb.co.uk/v35/n15/ian-hacking/lost-in-the-forest

> Sauvages’s dream of classifying mental illness on the model of botany

> was just as misguided as the plan to classify the chemical elements on

> the model of botany. There is an amazingly deep organisation of the

> elements – the periodic table – but it is quite unlike the

> organisation of plants, which arises ultimately from descent. Linnaean

> tables of elements (there were plenty) did not represent nature.”

JS

> Hacking is comparing three systems whose hidden structure is very different:

> mental illness, botany, and chemical elements. For each of them, that structure

> determines their observable properties. But different structures would lead to

> different methods of organization:

Yes, this is a very diverse set of things to consider together. When I read the article, I was a little surprised that he would pursue such a broad comparison.

> 1. Biological species are an extremely important, but *unusual*

> special case. The method of reproduction determines a tree,

> but very few non-biological classes are as strictly tree-like.

> Even bacteria, for example, can exchange genes with other bacteria.

> With modern methods of genetic engineering, the strict trees for

> other biological species can be broken down.

>

> 2. The so-called periodic table is the result of the "hidden structure"

> of atoms. But as physicists discover more about that structure,

> the simple table is becoming much more complex. Even Mendeleev's

> original "table" was more complex than a table.

>

> See http://www.aip.org/history/curie/periodic.htm

>

> 3. The DSM certainly can be and has been severely criticized for many

> reasons. The underlying causes and interrelationships among mental

> symptoms and their grouping into "illnesses" are mostly unknown.

> The structure of a printed book and its table of contents is a tree.

> But nobody knows the appropriate attributes or "primitives" that

> could generate that tree or a more appropriate classification.

>

> These observations about biological species, chemical elements, and mental illnesses

> can be repeated for *every* branch of human knowledge, experience, or activity –

> and for the terminology about them.

Yes. And the fact that the American Psychiatric Association has attempted such a classification shows that there is some fundamental underlying drive among smart educated people to create a classification of this type, somehow. Maybe there is a clue in these words “The structure of a printed book and its table of contents is a tree. But nobody knows the appropriate attributes or "primitives" that could generate that tree or a more appropriate classification.”

This point might go to my concern with developing more “primal” or “truly primitive” primitives – perhaps in terms defined in the “foundations of mathematics”, such as the Dedekind Cut, that links the rational numbers of real-world measurement to the continuous variation of the real number line that is seen by some as “beyond concepts”. Maybe we need a new model of what any concept really is. Georg Cantor defined a “set” as “a Many that allows itself to be thought of as a One”. http://en.wikiquote.org/wiki/Georg_Cantor

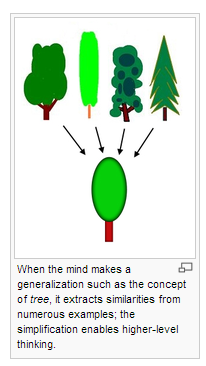

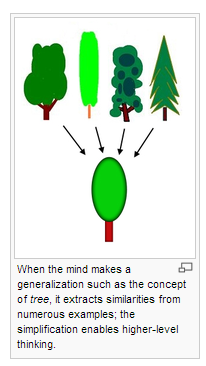

Maybe all basic concepts are a “many that is a one” (“different kinds of trees = tree”, “many trees = forest”), and a fundamental definition like this must undergird every math-based attempt to categorize and classify. So perhaps we would most usefully be approaching this subject at level beneath more traditional ideas of “classification” or “category”, and get into underlying and profound issues about how any sort of distinction or category at all can be formed. In the most primal and fundamental way – how is “A” distinguished from “B”? Dedekind’s Cut defines that distinction, and maybe we need to build all classification in an ascending hierarchy of dimensional cuts grounded in something this fundamental and basic.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Concept

SIMILARITIES AND DIFFERENCES

JS

> These are among the many reasons why I emphasize the weaknesses of

> any proposal for a single ideal, universal, all-purpose system for

> classifying everything that exists -- or all the ways of talking

> about everything that people want to talk about.

Yes – maybe – depending on exactly what you mean. Yes, there is huge diversity of systems and methods and purposes, and in many or most cases, those systems and methods and purposes may not be commensurate. So, let’s not try to create something that takes on this impossible task.

But just as we can identify numerous differences in approaches to conceptual structure – and see these different systems as incommensurate – it might also make sense to look for similarities among systems and methods and purposes – and, without blurring or ignoring differences, begin to clarity their common ground and their underlying similarities. That is inherently the “transcend and include” process for creating new higher categories or systems or methods. A kind “E Pluribus Unum” approach – that does not crush any hopes for unity simply because differences exist – but fully acknowledges those differences, yet still identifies common ground and similarity in a forceful and comprehensive way.

JS

> It's important to distinguish systems for classifying things,

> organizing things, finding things, analyzing things, and reasoning

> about things. Those are related, but different purposes.

> No single logic, ontology, or methodology could be ideal for all of them.

I like this quote, interpreting it as encouraging an innovative (new) and broadly integral approach that embraces everything known across all levels of psychology and philosophy.

It’s not just that contemporary A.I. hasn’t solved these kinds of problems yet; it’s that contemporary A.I. has largely forgotten about them. In Levesque’s view, the field of artificial intelligence has fallen into a trap of “serial silver bulletism,” always looking to the next big thing, whether it’s expert systems or Big Data, but never painstakingly analyzing all of the subtle and deep knowledge that ordinary human beings possess. That’s a gargantuan task— “more like scaling a mountain than shoveling a driveway,” as Levesque writes. But it’s what the field needs to do.”

“As he puts it, “There is a lot to be gained by recognizing more fully what our own research does not address, and being willing to admit that other … approaches may be needed.”

http://www.newyorker.com/online/blogs/elements/2013/08/why-cant-my-computer-understand-me.html

For me, it seems reasonable to pursue the development of a comprehensive model of cognitive structure that embraces both tree and net, that recognizes the nature of negotiated and stipulative definition, as well as bottom-up empirical observation, and builds an analytic model that recognizes and accommodates the natural presence of holistic data-blocks in normal cognition and natural-language semantics. Whether this model will rival Siri or Google voice-recognition is another question. But my guess is, a robust vision of conceptual structure based on a systematic analysis and integration of similarities among methods (such as many-to-one convergence across levels of abstraction), in a format that does not ignore or skip over differences, could be a powerful contribution to the broad task of pulling together the vast range of semi-independent languages and techniques that come together in the study of concepts and classification.